One of Daishi Miguel-Tanaka’s earliest memories is walking into his first grade class in California and being struck by how diverse the student body was.

“I saw kids of all shapes and colors holding their hands over their hearts [saying the pledge] under the American flag,” Miguel-Tanaka recalls. “That was huge for me. I fell in love with this country and I wanted to stay for the rest of my life.”

Miguel-Tanaka was born in Japan to a Japanese father and Filipina mother. His family faced discrimination for being mixed race and, in hopes of finding greater opportunity elsewhere, immigrated to the U.S. Miguel-Tanaka’s grandfather was already a U.S. citizen living in California and his family looked forward to being reunited.

Even without knowing much about America, Miguel-Tanaka dreamed of going to Harvard and becoming a lawyer. “My parents remembered me, as a young child, telling them I wanted to go to Harvard. I wanted an American education because America is a land of opportunity.”

Miguel-Tanaka’s family arrived in the states in 2004 when he was just six years old. They applied for a family reunification visa, which allows certain family members of U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents to reside in the U.S. and become permanent residents. While his family eagerly awaited updates on their immigration status, Miguel-Tanaka enrolled in school and immersed himself in all that America had to offer. But even as he excelled, quickly learning English and connecting with the larger immigrant community in California, his family’s immigration status always loomed large, like a shadow blanketing their new life.

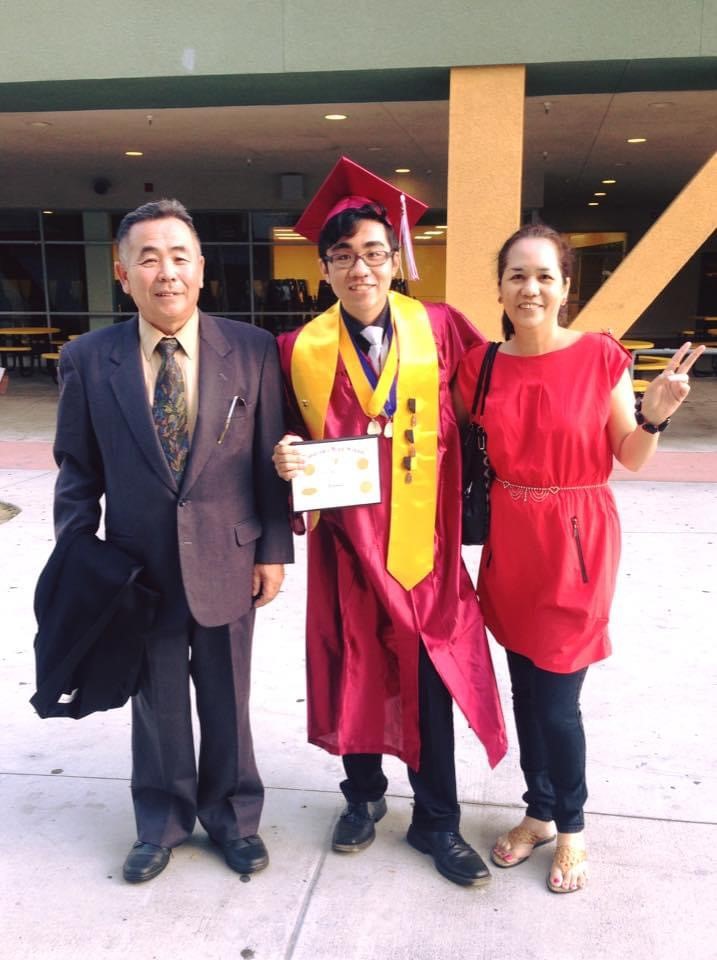

A photo of Daishi Miguel-Tanaka and his family.

“There were a lot of things that went unspoken [as an undocumented person], like the fact that we can’t travel outside the country or apply for the same jobs or opportunities,” Miguel-Tanaka says. “[My community] was really close because no one [who wasn’t an immigrant] quite understood how our immigration status affected us.”

At the time Miguel-Tanaka’s family applied for a reunification visa, there was a 25-year wait. While caught in that backlog, Miguel-Tanaka’s grandfather passed away and they lost eligibility for the family reunification visa. His family made the difficult decision to stay in America and become undocumented. While attempting to get a green card, his parents worked back-breaking jobs at nursing homes for pennies. Miguel-Tanaka remembers seeing his mother cry when her paychecks were withheld and she had no ability to fight back. His father, who took on driving responsibilities in the family, was not able to obtain a legal license. Miguel-Tanaka worried every time his father got behind the wheel that he’d be stopped and deported.

“It was just this constant anxiety,” Miguel-Tanaka says. “It was mentally and emotionally challenging to watch my parents struggle. I worried I wouldn’t be able to afford college or attend a university of my choosing.”

When Miguel-Tanaka was a teenager, the Obama administration introduced the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (DACA), an executive order that provides protection from deportation for undocumented people who were brought into the U.S. before the age of 16. DACA allowed Miguel-Tanaka to live out his childhood dream. He graduated from Harvard in 2019 and became the first in his family, and his high school, to get a degree from an Ivy League university.

While DACA allowed Miguel-Tanaka to chase his version of the American dream, its procedure and political volatility meant that his family was torn in two. “My parents made the difficult decision to self-deport and return to Japan for needed medical care,” Miguel-Tanaka says. “We were separated for seven years.”

Today, as one of just a few Japanese DACA recipients, Miguel-Tanaka is concerned about the Trump administration’s recent announcement that it would use the Aliens and Enemies act to deport people. That same act was used to intern Japanese Americans during WWII. When he thinks about how to channel his fear into hope, he thinks again about his parents and how watching them struggle has inspired him to find better ways to protect people.

A photo of Daishi Miguel-Tanaka.

“I’ve seen so much opportunity for positive change. I’ve seen people step up and organize. I’m really grateful to be part of the experiment, to constantly improve and provide equitable rights,” Miguel-Tanaka says.

Today, Miguel-Tanaka is the director of Immigration Policy & Research at FWD.us, a bipartisan advocacy organization focused on expanding protections for the undocumented, particularly DACA recipients. While a big part of his work is helping local governments and advocates combat immigration policies that negatively impact communities, his work is not purely reactive. There’s so much room, he says, to start building a positive, affirmative vision on immigration to counter the harmful policies the Trump administration has proposed.

“What is an alternative to mass deportation? What is the alternative to eliminating asylum?” Miguel-Tanaka asks, voicing the questions he’s focused on in his work. “At FWD, I talk to mayors and other stakeholders about how we can build our own power. I’m fortunate to work with people who want to fight back in spite of the political fallout.”

Finding state and local officials who are willing to engage proactively and positively on immigration gives Miguel-Tanaka hope that the work can focus less on the scare tactics coming out of the White House, and more on neighborhoods and communities.

“My parents have raised me to believe I can make a difference,” Miguel-Tanaka says. “‘Daishi’ actually means ‘great history.’ To me that means pursuing ambitious goals that help immigrants and my community.”

Our series, Behind the Fight for Our Rights, asks individuals defending our freedoms how they’re thinking about the next four years. Below, Miguel-Tanaka shares insight into his life – both professional and personal – under the Trump administration.

ACLU: What are you most looking forward to in the next four years? What gives you hope?

MIGUEL-TANAKA: What gives me hope is that we can increase attention toward what is happening in neighbourhoods and communities to focus immigration policy where it starts: with families at the dinner table.

ACLU: What is the biggest challenge you’re expecting in the next four years?

MIGUEL-TANAKA: Fear. Many public servants that I work with are afraid to speak up against the Trump administration and put a target on their backs. Trump has already talked about taking sanctuary cities hostage in exchange for cooperation with deportation efforts. So fear is a real challenge and I believe that hope is the counter to that fear.

ACLU: What do you wish people knew more about the fight for immigrants’ rights?

MIGUEL-TANAKA: I wish more people realized that debates about immigration span decades. Immigration can’t be a contemporary policy challenge, just like it can’t be isolated from our legacy of racism and xenophobia.

ACLU: What is one thing you wish you knew about the fight for immigrants’ rights?

MIGUEL-TANAKA: I really want to learn more about innovative models around employment. One of the biggest challenges we have right now are the millions who will lose work authorization. I want to know more about innovative, independent contracting models, cooperative models that open up new areas of opportunities for immigrants to sustain themselves and families.