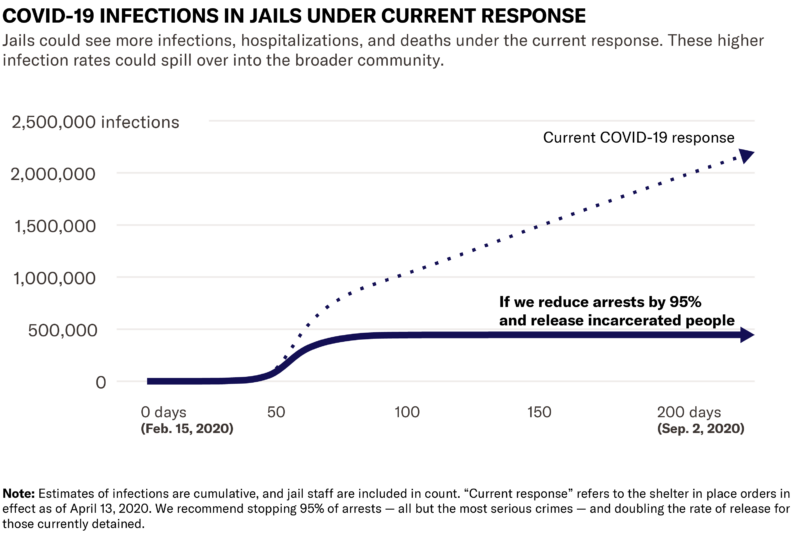

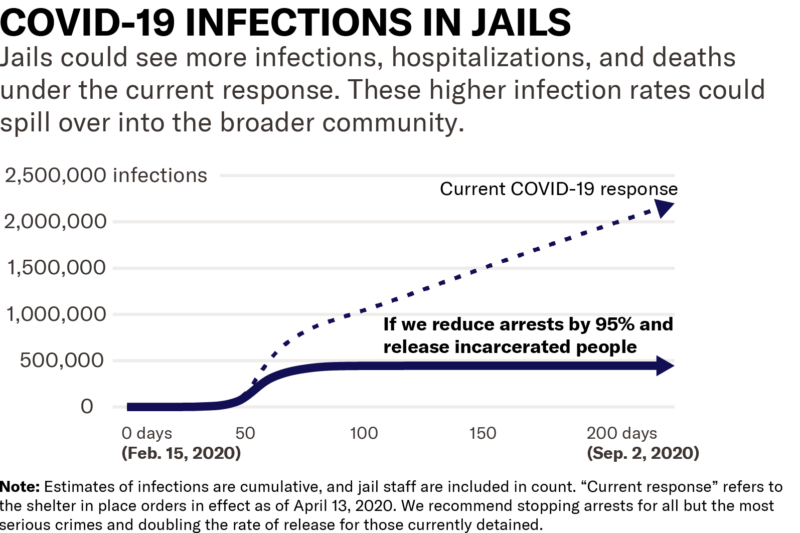

The Trump administration optimistically projects that “substantially under” 100,000 people will die from COVID-19 in the United States. Horrific as that statistic is, a new model suggests it could be a huge underestimate. The government models fail to consider the impact of the virus on the incarcerated population, who will be infected and die at higher rates. And any prison or jail outbreak is bound to spill over into the broader community — causing more people to die in the general public, too.

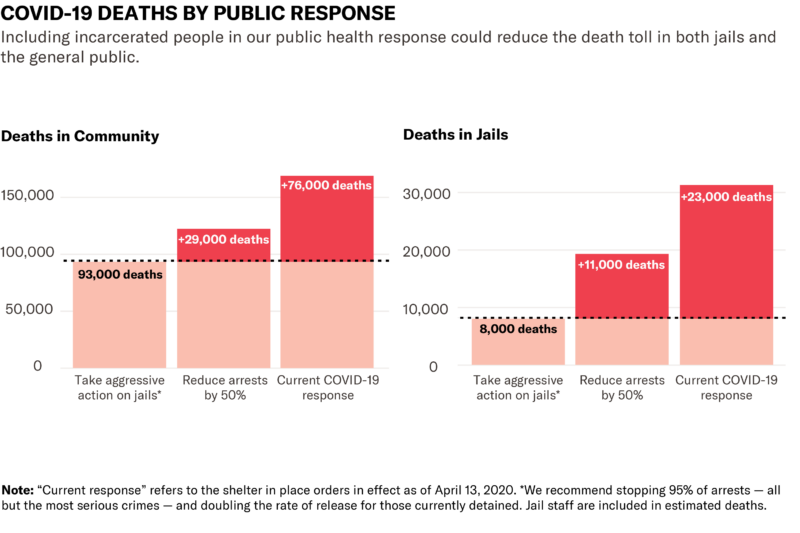

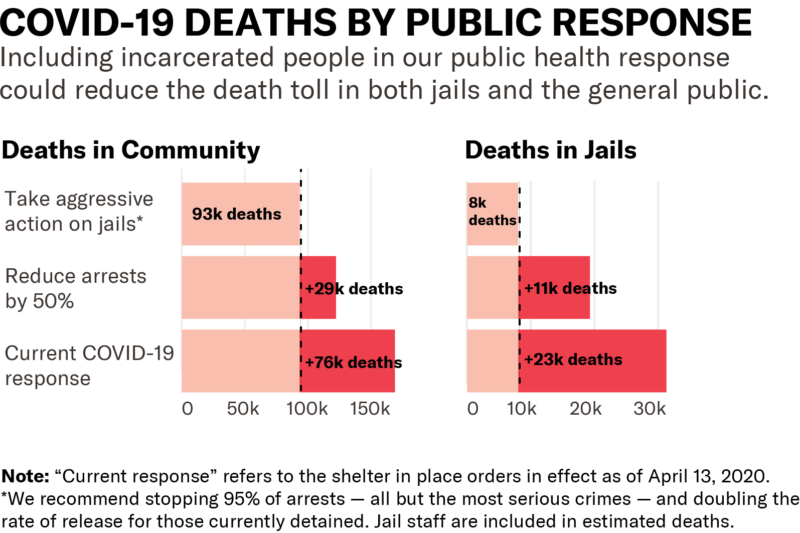

The ACLU partnered with epidemiologists, mathematicians and statisticians to create a first-of-its-kind epidemiological model that shows that as many as 200,000 people could die from COVID-19 — double the government estimate — if we continue to ignore incarcerated people in our public health response. But we have the power to change this grim outcome. We can save as many as 23,000 people in jail and 76,000 in the broader community if we stop arrests for all but the most serious offenses and double the rate of release for those already detained.

The risk that COVID-19 poses to incarceration facilities is well-documented. Overcrowding, lack of access to hygiene, and substandard health care make jails and prisons potential time bombs for any outbreak, let alone the deadly coronavirus. But what often gets lost in the discourse is the connection between incarceration facilities and the broader community. Correctional staff come to work every day and then return home. People are frequently brought in on arrest and released if they can pay bail, or held for short stays. Any of these individuals can easily and unknowingly bring the virus into a jail, where infections can spread rapidly. And because of this constant flux of people, more sick people in jail will result in more sick people in the general public.

While all of us will be impacted by inaction, communities of color will feel it most. Black and Brown people are overrepresented in jails and prisons due to long-entrenched racial bias in the criminal legal system, as well as low-income communities. Most correctional staff are also people of color, who will return to families and communities of color while potentially carrying the virus. There is already ample evidence that Black people are dying at much higher rates in major cities across the country. We can expect even more racial disparities in COVID-19 deaths if we allow the virus to spread freely throughout jails.

But these statistics don’t have to be death sentences. We can flatten the infection curve and decrease infection rates for all of us by reducing the number of people we incarcerate. It’s easier than it may seem. Hundreds of thousands of people are sitting in jail simply because of technical violations, their inability to pay fines and fees, or because they can’t post bail. There is no reason these people should be locked up even under normal circumstances. During the pandemic, the need for reform is more urgent than ever.

Governors, judges, sheriffs, and chiefs of police can reduce jail populations without changing the law. They should use the powers of their office to stop arresting and incarcerating people for low-level offenses and release those who are vulnerable to COVID-19 due to age or health conditions. Taking these measures would significantly reduce the spread of COVID-19 in jails and thus reduce the death toll for all of us.

- If we stop arresting people for minor offenses (cutting arrests by half), we can save up to 12,000 lives in jails and 47,000 lives in surrounding communities.

- If we stop arrests for anything but the five percent of crimes defined as most serious by the FBI — including murder, rape, and assault — and are able to double the rate of release for those already detained, we can save 23,000 lives in jails, and 76,000 lives in communities.

These critical reforms are more urgent than ever, but they were needed long before the pandemic. The U.S. incarcerates more people than any other country on earth, with four percent of the world’s total population and 21 percent of the world’s incarcerated population. Further, reforming our incarceration and policing system would go a long way toward reducing inequalities and systemic harm faced by communities of color, who were already over-policed and overrepresented in jails and prisons to begin with.

The ACLU has responded by creating a model executive order and pressuring governors to adopt it, as well as pushing prosecutors and sheriffs to use the power of their offices to reduce jail and prison populations. As a result of these efforts, 16,000 people have either been released or not incarcerated in the first place, and governors have made 15 executive actions. And according to an ACLU poll, there is strong bipartisan support for releasing people from prisons and jails, with 63 percent of respondents supporting the action.

Taking critical steps toward reform will save lives. Colorado, for example, has reduced its jail population by 31 percent and as a result, will save 1,100 lives and could cut the state’s death toll by a quarter.

What the numbers don’t show, however, are the individuals who have already faced the impact of our inaction. The ACLU has partnered with the UCLA Prison Law and Policy Program to create a directory of all the people who have died to COVID-19 while incarcerated. Every day that passes without initiating these vital incarceration reforms means that more people will die, and this list will grow. These are more than numbers.

COVID-19 has already changed the way we live and function as a society in ways that would have been unimaginable just a month ago. There is no reason to exclude prisons and jails from these radical changes — especially in a country that incarcerates more of its people than any other country on earth. It’s time for the government to act in the name of public health. Failing to protect incarcerated people will hurt all of us.

ACLU analysis was led by Aaron Horowitz, chief data scientist, and Brooke Madubuonwu, director of legal analytics and quantitative research.

Udi Ofer, Director, Justice Division, ACLU National Political and Advocacy Department

Lucia Tian, Chief Analytics Officer, ACLU