Mikal Mahdi committed two tragic murders in 2004 when he was only 21. This Friday, more than two decades later, South Carolina plans to execute him for his crimes, despite serious constitutional and moral questions that call for the Supreme Court to stay his execution. If carried out, Mikal’s execution will be the third in South Carolina this year, and the 12th execution nationwide.

Without a doubt, Mikal’s crimes caused irreparable harm, but justice requires a fair trial and sentencing.

Mikal’s story is a tragic one of a child failed by everyone at every turn. As a toddler, Mikal witnessed his father routinely and viciously beat his mother. At age four, his mother fled, leaving Mikal and his brother to become the target of his father’s abuse. By age eight, Mikal was suicidal. At age 14, he was sent to juvenile detention for property crimes. After serving his time, however, his father failed to take him to required court and other program meetings. He was incarcerated again and thrown into solitary confinement—a practice now largely understood as a form of torture, particularly for children. At trial, his attorneys declined to present key details about his life to the court, including his long history of childhood abuse, neglect and abandonment.

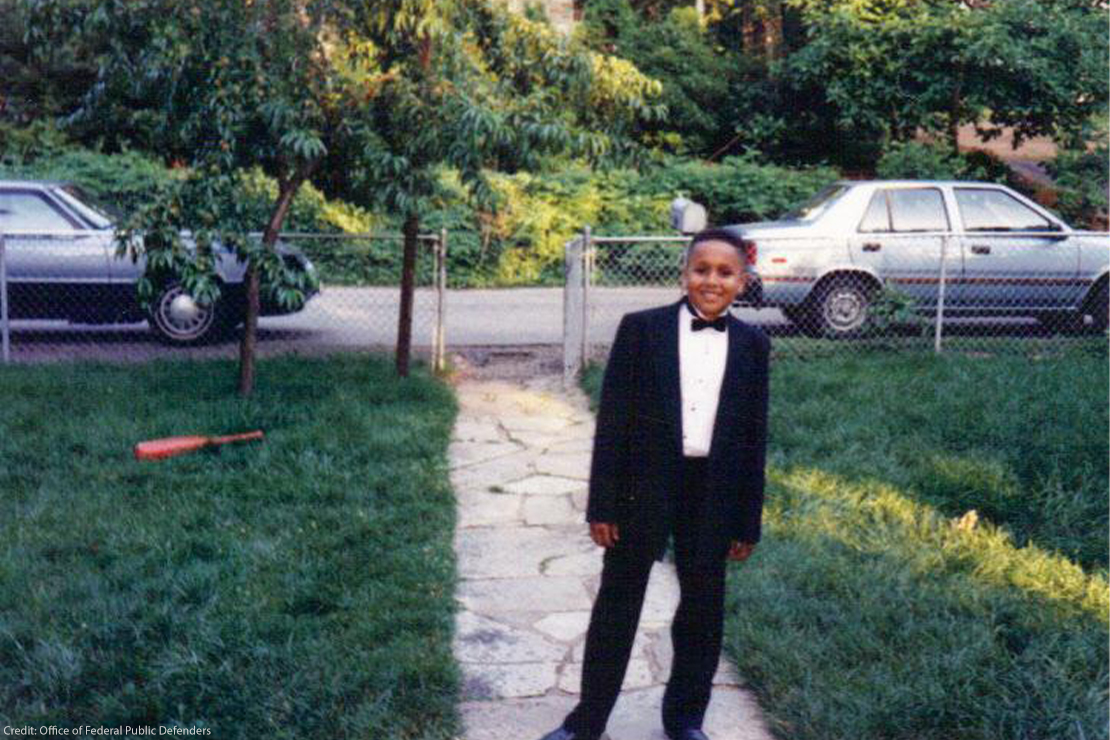

Mikal Mahdi as a middle-schooler posing in a tuxedo.

Credit: Office of Federal Public Defenders

Today, at 42, Mikal is remorseful and accepts responsibility for crimes he committed when he was 21. He has been denied life without parole, and the state intends to execute him Friday, April 11th. His traumatic childhood, at home and in custody, shaped his life and actions and should have been a key factor in the state’s decision, yet his trauma was not considered. It is a profound injustice that, today, the system that has consistently failed Mikal at every turn now ignores those failures when determining whether he should live or die.

Mikal grew up in an abusive home where violence was commonplace. One of Mikal’s earliest memories is of his father slamming his mother through a glass table. After his mother fled this abuse, Mikal’s father told him she was dead. Left in his violent and mentally ill father’s care, Mikal suffered years of physical and emotional abuse at home. At age eight, Mikal showed signs of severe depression and suicidal ideation. At age nine, Mikal watched his father kidnap and assault his mother at gunpoint. At age 11, his father unenrolled him from school, and kept him at home for daily survivalist training in the rural woods where they lived.

For many years now, the Supreme Court has recognized that the criminal legal system should treat children differently than adults.

As a teen, Mikal’s mental health continued to decline. He was diagnosed with depression. He expressed suicidal ideation repeatedly and was placed on suicide watch multiple times. Instead of receiving the mental health care he needed, Mikal was thrust into the prison system at 14. He spent the rest of his childhood and young adulthood in custody, alone. From 14 to 21—key years for brain development—he spent a collective 8,000 hours in solitary confinement, including one stretch of 1,700 consecutive hours (more than two months), and another stretch of 500 hours (three weeks).

While incarcerated, Mikal was put into isolation for typical adolescent behavior, like untucking his shirt, swearing, refusing haircuts, and ripping out book pages. He was tased, shot with rubber bullets, and subjected to racial slurs. He was denied educational, rehabilitative, and therapeutic programs. By the time Mikal was released, he left with worsening mental illness, deep trauma, and no support system. Two months later, he committed the crimes for which he now faces execution.

Allowing Mikal’s execution to proceed is beyond a failure of justice.

For many years now, the Supreme Court has recognized that the criminal legal system should treat children differently than adults. Because kids are still developing physically, psychologically, and neurologically, the legal system sees them as having less culpability for their actions and a greater capacity for reform. For those reasons, juvenile detention is supposed to be rehabilitative. Developmental psychology and neuroscience further support the need for rehabilitation, recognizing that our brains continue to develop into our mid-twenties. However, as a child, Mikal’s time in custody was far from rehabilitative. We now know that placing kids in solitary confinement for even a few days can lead to permanent cognitive and behavioral impairment. Isolation can irreversibly change neural pathways and neurochemistry, altering areas of the brain responsible for regulating emotions and memory.

No court has ever considered Mikal’s full story, even though the law requires that all relevant mitigating evidence be presented to ensure a fair and just sentencing process. Because the death penalty is final and irreversible, capital trials demand the highest level of diligence, insisting on an unflinching look into the person’s life history and circumstances before a sentence can be imposed. But Mikal received a death sentence from a judge who heard less than 30 minutes of testimony about his upbringing. His lawyers did not call a single witness who could testify firsthand to the potential he showed as a young child, and they presented only 15 transcript pages of mitigating evidence at trial—a shockingly brief presentation for a life-or-death decision. Thus, the court was not only deprived of the many facts detailing the trauma of Mikal’s youth, but also the scientific evidence that would have shown the impact it had on a young, developing brain. The court had no window into how those years of abuse, isolation, and systemic violence shaped Mikal’s path.

Allowing Mikal’s execution to proceed is beyond a failure of justice. It is a statement that we’re willing to abandon children, deny them care, and then punish them when they break under the weight of that neglect. We can and must do better. The Supreme Court has the opportunity now to stop the cycle of neglect and abandonment that has defined Mikal’s life and experience with the legal system. It should choose to recognize the humanity of the child that the system failed to protect.

Learn more about how to support Mikal's clemency effort here.