This post also appears in Cosmopolitan.

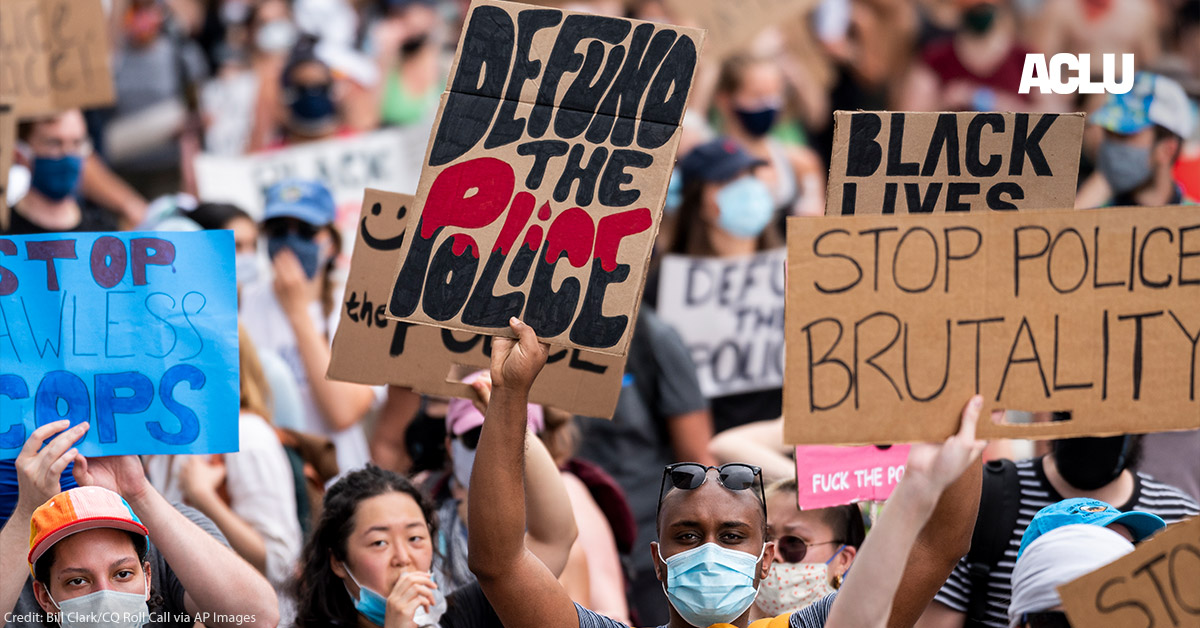

Almost exactly six years after NYPD officers murdered Eric Garner in New York City, Minneapolis police officers murdered George Floyd. Activists, advocates, and protestors are still screaming “I can’t breathe” and begging government officials for police reform that will end police violence in Black communities. But today’s demands are bigger and bolder: Now, protesters are advocating for systemic changes that require a complete reimagining of law enforcement in the United States.

American policing has never been a neutral institution. The first U.S. city police department was a slave patrol, and modern police forces have directed oppression and violence at Black people to enforce Jim Crow, wage the War on Drugs, and crack down on protests. When people ask for police reform, many are actually asking for this oppressive system to be dismantled and to invest in institutions, resources, and services that help communities grow and thrive. That’s why many protestors and activists, following in the footsteps of Black-led grassroots groups, are demanding immediate defunding of police departments.

The idea of defunding, or divestment, is new to some folks, but the basic premise is simple: We must cut the astronomical amount of money that our governments spend on law enforcement and give that money to more helpful services like job training, counseling, and violence-prevention programs. Each year, state and local governments spend upward of $100 billion dollars on law enforcement—and that’s excluding billions more in federal grants and resources.

Budgets are not created in a vacuum. They can be changed through targeted advocacy and organizing. We can demand that our local officials (including city council members and mayors) stop allocating funds for the police to acquire more militarized equipment and instead ask for that money to go toward community-run violence-prevention programs.

We can demand that our federal government redirect the money that funds police presence in schools to putting counselors in schools instead.

Funneling so many resources into law enforcement instead of education, affordable housing, and accessible health care has caused significant harm to communities. Police violence is actually a leading cause of death for Black men: A recent study found that 1 in 1,000 Black men can expect to be killed by police, and public health experts have described police violence as a serious public health issue. For a country like ours, which considers itself a modern democracy that pushes ideals of freedom and justice for all, that number should be truly shocking.

We can demand that our federal government redirect the money that funds police presence in schools to putting counselors in schools instead.

Funneling so many resources into law enforcement instead of education, affordable housing, and accessible health care has caused significant harm to communities. Police violence is actually a leading cause of death for Black men: A recent study found that 1 in 1,000 Black men can expect to be killed by police, and public health experts have described police violence as a serious public health issue. For a country like ours, which considers itself a modern democracy that pushes ideals of freedom and justice for all, that number should be truly shocking.

We have little evidence, if any, to show that more police surveillance results in fewer crimes and greater public safety. Indeed, funneling police into communities of color and pushing officers to make arrests just perpetuates harm and trauma. Yet since the 1980s, spending on law enforcement and our criminal legal system has dramatically outpaced that in community services such as housing, education, and violence prevention programs. Those are the institutions that help build stable, safe, and healthy communities.

For example, Los Angeles’s budget gives police $3.14 billion out of the city’s $10.5 billion. Spending on community services such as economic development ($30 million) and housing ($81 million) pale in comparison to the massive LAPD budget. (On Wednesday night, after years of Black Lives Matter grassroots activists demanding a cut in LAPD’s budget, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti announced he would cut $100 million to $150 million from the LAPD budget and reinvest those funds in communities of color.) Similarly, in New York City, the government spends almost $6 billion on policing, which is more than it does on the Department of Health, Homeless Services, Housing Preservation and Development, and Youth and Community development combined.

By shrinking their massive budgets, we can help end decades of racially driven social control and oppression as well as address social problems at their root instead of investing in an institution that further oppresses and terrorizes communities.

In addition to divesting from police and reinvesting the savings in nonpunitive programs that benefit public safety and health, there are other critical steps we need to take to foster the systemic change people across the country are calling for:

- End enforcement of minor offenses that drive street-level harassment. We can do this by repealing laws across the country that criminalize minor behaviors and passing laws that legalize activities such as marijuana possession and distribution.

- End the presence of police in schools, which exacerbates racial inequalities, puts immigrant students at risk of deportation, and limits opportunities accessible to low-income students. (Minneapolis Public Schools just voted to end its contract with the city’s police department.)

- Develop mobile crisis services, peer crisis services, and crisis hotlines and warmlines (where people can call when they just need to talk to someone who understands what it’s like to live with mental health problems) to support people who have a behavioral or mental health crisis.

- Ban pretextual stops and consent searches that act as common mechanisms for police to engage in racial profiling and circumvent legal standards.

- Implement common-sense, civilly and criminally enforceable legal constraints so there will be only rare instances in which officers are able to use force against community members.

For too long, the focus on police reform has been dominated by reforms that try to reduce the harms of policing rather than rethink the overall role of police in society. But six years after the Black Lives Matter movement rose to national attention, activists across the country are coming together to demand what many have known has been the solution all along: defund the police.

Paige Fernandez, Policing Policy Advisor, ACLU

https://www.aclu.org/news/criminal-law-reform/defunding-the-police-will-actually-make-us-safer