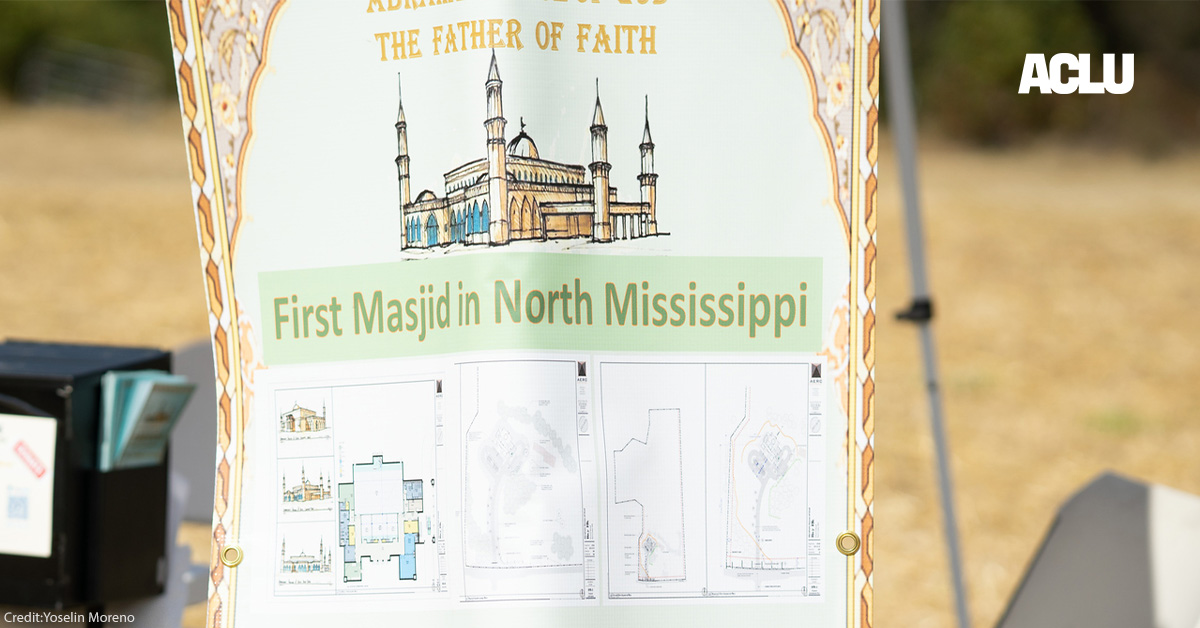

Last Sunday marked a historic and joyful day in DeSoto County, Mississippi. The county’s first mosque, the Abraham House of God, finally broke ground in the City of Horn Lake. While the occasion was celebratory, it was also a relief to the mosque’s founders, who were forced to sue last year after city officials — motivated by anti-Muslim prejudice — denied them a critical zoning authorization.

Represented by the ACLU, the ACLU of Mississippi, and Simpson Thacher & Bartlett LLP, the mosque and its founders argued in a 2021 lawsuit that the zoning decision violated both the First Amendment, which prohibits singling out one faith for discriminatory treatment, and the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA), a federal law that provides heightened protections for religious groups seeking to establish a house of worship or to use property for other religious purposes. In a decisive victory, our clients quickly won a consent decree (a court order to which the parties agree) requiring the city to approve their construction site plan and prohibiting further discrimination against them.

Attendees gather during the mosque’s groundbreaking ceremony.

Yoselin Moreno

But that didn’t stop Horn Lake from once again trying to thwart our clients’ right to develop their property. In April, our clients applied for a conditional-use permit to establish an Islamic cemetery next to the mosque. Although the city’s Planning Commission staff “strongly and categorically” recommended approval of the application, some commissioners balked. Echoing the biased sentiments expressed nearly a year before by a city Alderman who voted against the mosque’s site plan, one planning commissioner complained, “I am assuming that Muslims nationwide will be coming to Horn Lake to bury their dead.”

It was only after we intervened, yet again, and reminded the city that it must comply with the First Amendment, RLUIPA, and the consent decree, that the Planning Commission voted 4-3 to recommend approval of the permit. And, last week, the Board of Aldermen voted in favor of the recommendation, ensuring that the mosque will be able to offer vital funeral and burial services for the local Muslim community.

The Horn Lake matter is not the only recent incident in which minority-faith groups or houses of worship have faced discriminatory hurdles in zoning proceedings. In some instances, as in Horn Lake, the prejudice is overt and unmistakable. In others, the bias may be more veiled, cloaked in vague — and unsupported — allegations that the proposed land use will cause problems with parking, traffic, or noise.

Planting a magnolia tree during the groundbreaking ceremony.

Yoselin Moreno

This past summer, the ACLU and the ACLU of Rhode Island stepped in to represent the Horn and Cauldron, Church of the Earth, a small Wiccan church located in Coventry, Rhode Island. Wicca is a nature-based religion, and the church’s religious services, educational classes, and other faith-based activities focus on the relationship between the earth and the divine. As in Horn Lake, the Coventry Planning Commission staff recommended approval of our clients’ permit application, noting that the application met all requirements and that “the church has been holding activities on the property for many years and the Planning and Zoning department has not received any complaints since the church’s founding.”

Nevertheless, during a public hearing, members of the Coventry Zoning Board of Review declined to approve the permit, citing inaccurate parking concerns (the church has more-than-adequate parking for visitors) and unsubstantiated allegations about fire safety (the church follows all fire-safety laws, and the facilities comply with the fire marshal’s directives). When we became involved, it was clear that town officials either were not aware of, or did not care about, their obligations under RLUIPA, let alone under the First Amendment. Earlier this month, in response to our advocacy, the zoning board granted the church’s permit.

Unfortunately, some zoning discrimination matters are not resolved so quickly. In 2016, the Thai Meditation Association of Alabama, a Buddhist religious organization, filed suit after the City of Mobile repeatedly stymied its attempts to develop a meditation center on a 100-acre parcel of property. The complaint argued that’s the city’s denial of zoning approval bowed to community animus against Buddhism — to some, an unfamiliar faith. The case has dragged on for years, with a court recently finding that city officials made deceptive statements, violated local ordinances, failed to account for the religious nature of the proposed use, and “manipulated the reasons that the planning approval was denied,” including by drafting false meeting minutes. As the lawsuit proceeds, the ACLU and a number of other civil-rights and religious-freedom groups recently filed an amicus brief in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, supporting the Association’s claims.

Attendees greet each other at the groundbreaking ceremony.

Yoselin Moreno

Even if the Association ultimately prevails, however, it will come at great cost, as we have seen with our own clients. Challenging discriminatory zoning decisions often requires religious groups to tap into limited financial reserves. Moreover, every day that zoning approvals are wrongfully denied is another day that the religious groups or houses of worship are prevented from fully exercising their faith in fundamental ways. And because zoning matters are deeply rooted in and tied to the local community, the distress and dignitary harm that minority-faith applicants suffer from discriminatory denials hits that much closer to home.

That’s why we’ll continue to defend the right of all faiths — especially those that may be unfamiliar to some or unpopular in the eyes of others — to be free from unfair treatment in zoning proceedings. It’s not only the law; it’s the right thing to do.

Date

Friday, October 28, 2022 - 4:15pmFeatured image