After the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade last June, anti-abortion politicians didn’t just leap at the opportunity to ban abortion — they also threatened our ability to freely share information about abortion and reproductive health care, including in artwork and other forms of creative expression.

That’s what happened in Idaho when the Lewis-Clark State College Center for Arts and History removed six pieces of art depicting abortion and reproductive health care from an exhibition titled “Unconditional Care: Listening to People’s Health Needs.” The college based its decision on the state’s No Public Funds for Abortion Act (NPFAA), which prohibits the use of public funds for abortion, including in relation to speech that would “promote abortion” or “counsel in favor of abortion.”

Show curator Katrina Majkut, who also had work displayed in the exhibit, says rumblings of concern over the six pieces of art began about a week before the exhibit was set to open, but the artists were not informed their work would be removed until days, or even hours, before the show opened.

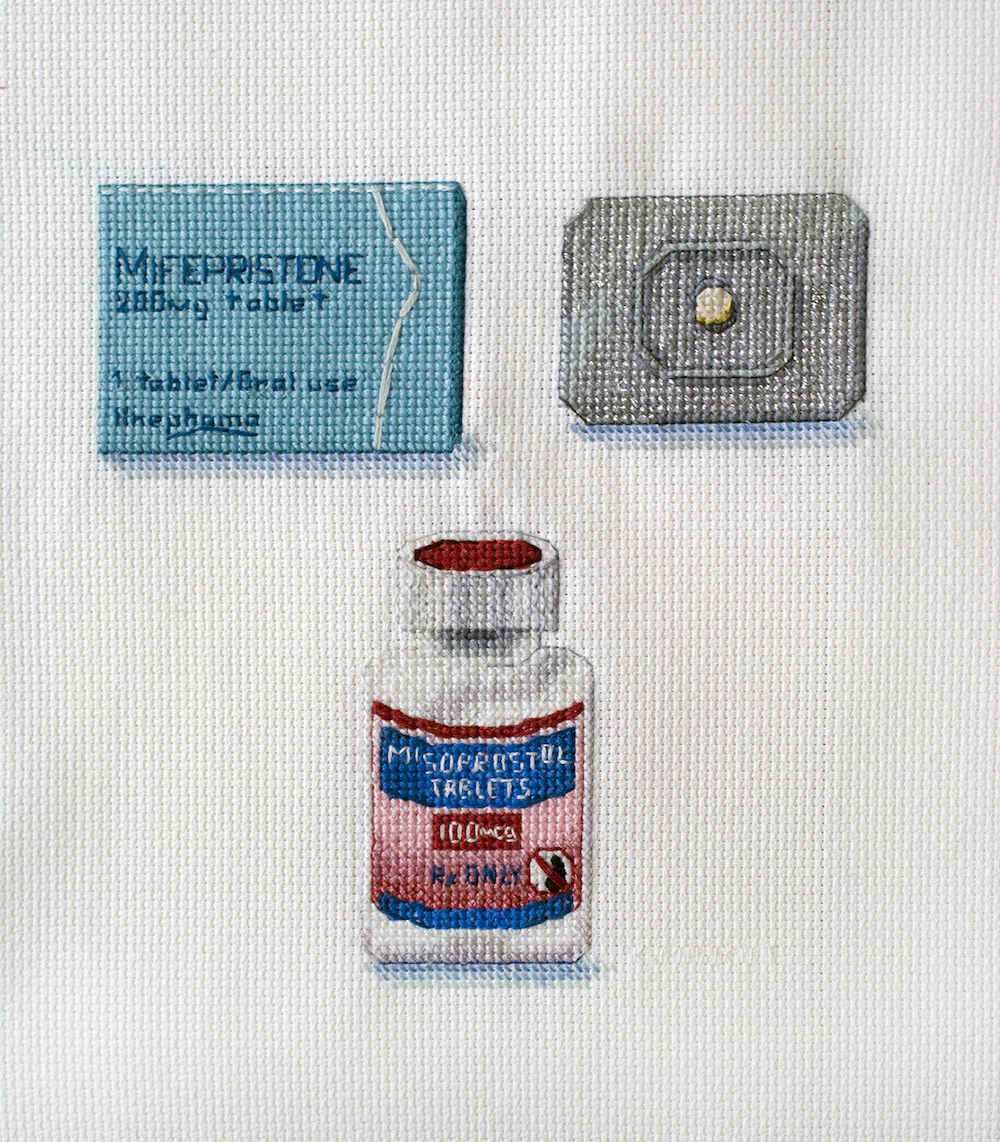

Medical Abortion Pill by Katrina Majkut

Thread on aida cloth, 11 x 14 in., 2015

The censored works include a series of documentary videos from artist Lydia Nobles where people share their experiences with pregnancy, abortion and reproductive care; a handwritten copy of one of the 250,000 letters addressed to Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger from artist Michelle Hartney; and a piece of embroidery from artist and show curator Katrina Majkut that shows two pills used in medication abortion, Mifepristone and Misoprostol.

The ACLU, the ACLU of Idaho, and the National Coalition Against Censorship condemned this act of censorship in a letter to Lewis-Clark State College President Cynthia Pemberton. The letter stated that the decision to pull works of art documenting women speaking honestly about their experiences with pregnancy and abortion is censorship, which deprives the public of a critical opportunity to engage in a broader conversation about these important topics. The letter also explained that it jeopardizes a bedrock First Amendment principle that the state refrain from interfering with expressive activity because it disagrees with a particular point of view.

Nobles, Hartney, and Majkut spoke to the ACLU about the pervasive harm that censoring any art, but especially art that examines abortion and reproductive health care, can have on entire communities. These interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

Q: What was your initial reaction when you found out your work would be removed?

MAJKUT: I was in disbelief. I figured school administrators knew better than to censor art, or to egregiously apply an anti-abortion law that is meant to stop actual abortion — something we weren’t even remotely doing — to censor art. It seems I underestimated the level of fear administrators had in facing fiscal and legal retribution from Idaho’s anti-abortion lawmakers, and I overestimated administrators’ commitment to academic freedom and education over irrelevant laws and money. It was surreal to watch it all go down and to realize that I and the other artists had been put in this unwelcomed and unfair position.

HARTNEY: I didn’t know about the [NPFAA] so I was shocked that my work was censored, especially because the project is not really about abortion, it’s about birth control. It’s already hard for a lot of people who have had abortions to talk about it, and this law makes it seem like we’re saying “there’s something wrong with abortion.”

NOBLES: Despite my own personal growth and advocacy for abortion rights, I still felt the pervasive stigma surrounding abortion. Here I am, someone who has had an abortion, created art about abortion, spoken publicly about abortion, and whose life was saved by an abortion, yet I still found myself feeling shame because discussing abortion with friends, family, and even in educational settings — where information should be fact-based, unbiased, and honest — remains challenging.

Sculpture by Lydia Nobles

Bolt and nut, flooring, latex tubing, Planned Parenthood waiting room chair, plexiglass discs, rubber piping insulation, 20″ x 18″ x 31.5″, 2019.

This sculpture was inspired by Lydia’s own abortion in late 2018 and was featured in the Brooklyn Museum event.

Q: In your opinion, how does this kind of censorship harm the ability to have honest conversations about reproductive health care?

NOBLES: It propagates a narrow, one-sided, prejudicial perspective that completely undermines the free exchange of ideas. It eviscerates a fundamental human right: our ability to speak. It’s like saying, “we don’t trust you.” Consider DeZ’ah [from Nobles’ documentary series] recounting the realities of being 25 and having two kids, and then becoming pregnant with twins. Twenty-five years old and suddenly she could potentially have four kids. It’s just not financially realistic. Students at Lewis-Clark State College were robbed of the opportunity to listen to DeZ’ah and create their own viewpoint.

MAJKUT: Abortion is part of comprehensive health care. It is a procedure that has been used for centuries to manage pregnancies. People can make it illegal, but the long-term existence of abortion shows that it is here to stay regardless of anti-abortion laws.

Q: Since Roe v. Wade was overturned last year, lawmakers have started reviving and enacting laws that criminalize abortion, and worked to suppress speech about abortion or reproductive health care. This includes sharing knowledge about abortion rights or access, and telling abortion stories.

In this environment, why is it important to you to share artwork that expresses experiences with abortion, pregnancy and reproductive health care? Why does abortion inspire you as a topic for art?

NOBLES: What inspires me is [interview subjects] like Blair. It inspires me to see Blair sitting down in her family room, on Zoom, recounting how she was so happy to be pregnant with twins. She wasn’t even married yet, and she didn’t even care. She was in love and pregnant. When she found out one of the fetuses wasn’t viable, she was crushed. I was crushed listening. It was one of the most challenging interviews I have done. You don’t listen to Blair’s story and walk away thinking abortion isn’t health care.

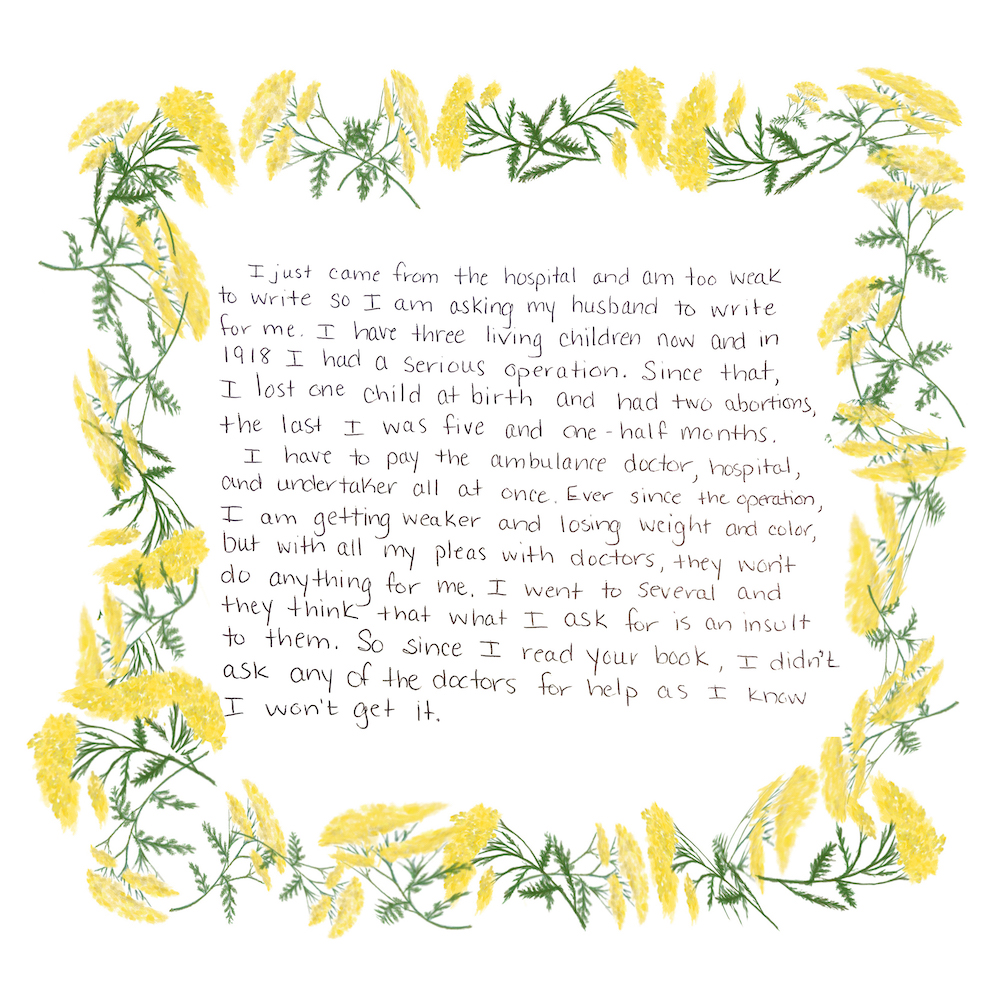

HARTNEY: The stories in my art are so important because they’re a first-hand account of the harms that people with uteruses faced when birth control was not only illegal, but sharing information about reproductive health care was also criminalized. That was 100 years ago. Since then abortion has been legalized, but now that right is being taken away. Birth control is the next right that could be taken away.

MAJKUT: “In Control’s” commitment to stitching every modern medical product in an objective and medically-accurate way means that the series becomes an artful sex/health education for viewers. This is particularly important for anyone who had abstinence-only sex education, no sex education, or sex education from biased or uninformed sources. Understanding how [reproductive health care] works and what tools can be used to manage our bodily functions and health needs is essential to living a full, happy, and long life.

With All My Pleas With Doctors They Won’t Do Anything 2023 from the installation Unplanned Parenthood by Michelle Hartney

11×11” archival inkjet print.

Unplanned Parenthood is a mixed media installation about the history of birth control and the role racism played in the fight for reproductive justice in the United States.

When students are robbed of a comprehensive health education, it will become that much harder to navigate health concerns later in life and that can create a cascade of problems in other areas of their life as well.

Q: More broadly, art and politics frequently intersect. Why is art such a powerful tool of political dissent?

NOBLES: Art is a powerful tool of political dissent because it creates space for people to experience themselves and others without judgment. You’re allowed to be a little bit crazy and wild, and people love that; it activates your brain in a different way. My work, for example, utilizes abstraction to create conversation about reproductive advocacy. You can look at the sculpture and relate it to your own life experiences and feelings, without knowing the entire meaning. Or you can read about the work, watch the films, and create an interpretation from there. It’s all how you want to engage, there’s no rules.

Q: This is not the first time artistic expression has been censored. We’ve seen it across the country with book bans, anti-drag legislation, and more. How does censorship affect our ability to tell diverse stories? How does it make ordinary experiences into something shameful or “taboo”?

HARTNEY: Censorship severs the important conversations that need to be out there in the world, and that’s only going to delay progress at a time we can’t afford to delay any progress. It’s also such a distraction. All these efforts to censor materials distract us from the work we’re doing, or make us too exhausted to keep doing the work, and that’s what conservatives want.

MAJKUT: When stories, facts, and art are censored and forbidden from being expressed, those American values start to disappear and the foundation of this country starts to crumble. Ignoring, silencing, or rewriting the stories of people are the acts of authoritative dictatorships. It breeds an unwillingness to recognize, to acknowledge, or to fix unhealthy actions and behaviors. That culture breeds hate, distrust, bias and lacks empathy, generosity, and kindness.

Date

Tuesday, March 21, 2023 - 11:00amFeatured image