My Native American first-grader Logan loves his long braid. It connects my son to our cultural and spiritual traditions as members of the Waccamaw Siouan Tribe of North Carolina. For thousands of years, male members of our tribe have worn their hair long. It is our spiritual belief that a person’s hair is a part of the spirit of the person. With his hair arranged in a long braid running down his back, Logan is confident and proud.

Logan goes to school at Classical Charter Schools of Leland in North Carolina (formerly called Charter Day School). I chose that school because the teachers are really focused on educating the kids. The school requires boys to keep their hair off the collar and not below the top of the ears, so Logan has worn his long hair in a bun. This compromised his beliefs, but it appeared necessary to meet the school’s standards. For all of kindergarten and most of first grade, Logan has attended school with his long hair in a bun without incident.

A few weeks ago, my husband and I were told that Logan’s hair was deemed “faddish” by school officials and in violation of the school’s “grooming standards” for boys. My son overheard his teacher say that he would have to cut his hair, which made him feel very sad. When I asked a school administrator why boys had to have short hair to come to school, I was told, “We want them all to look the same.”

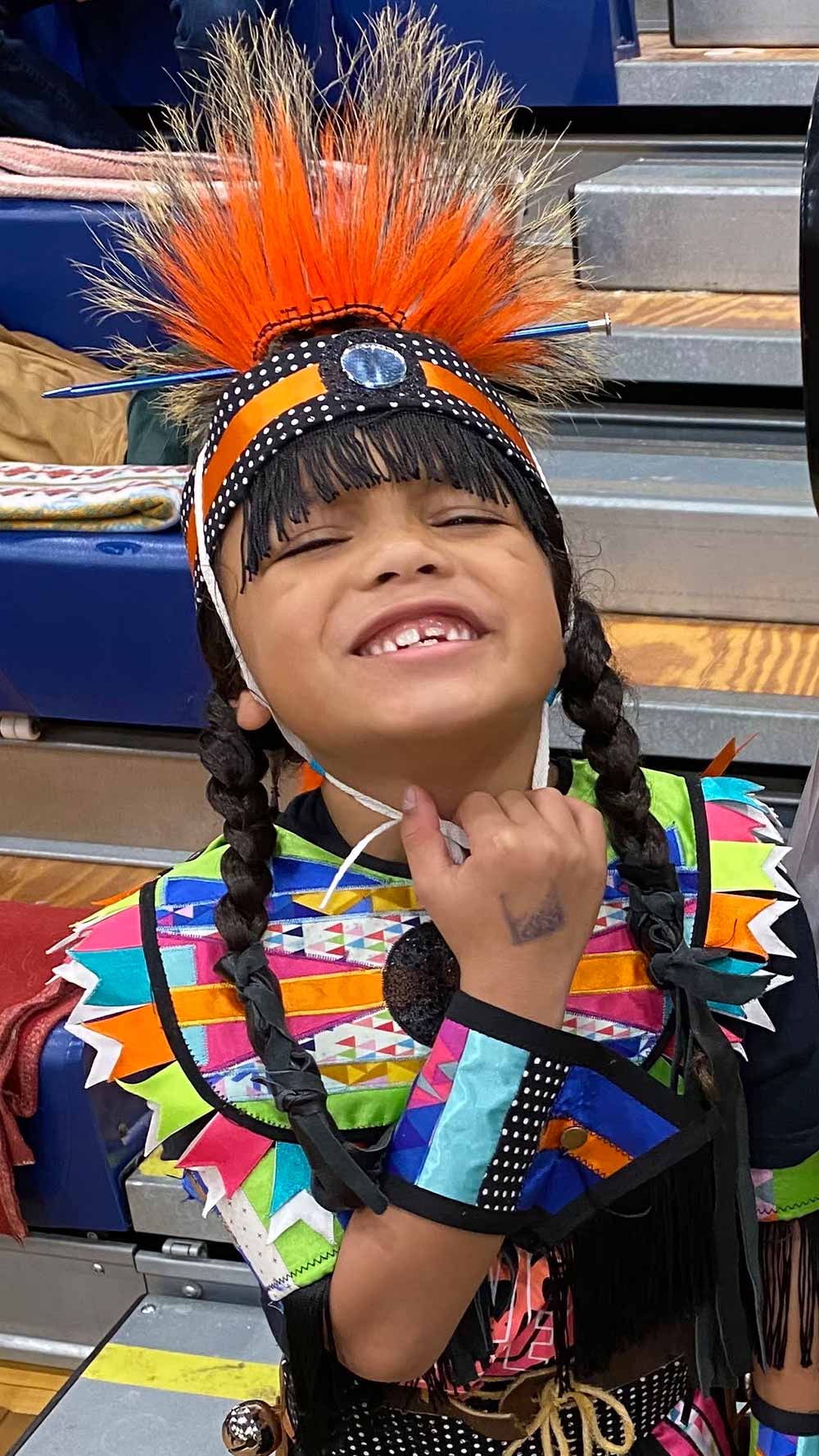

Logan, with his hair in braids, dressed in the traditional clothing of the Waccamaw Siouan Tribe.

Credit: Ashley Lomboy

The definition of faddish according to Webster’s dictionary is “intensely fashionable for a short time.” Native Americans have been wearing their hair long — whether it is for ceremony, in preparation for protecting our tribe, or as part of our tradition — since time immemorial. For more than 1,000 years, the Waccamaw Siouan tribe has and continues to steward the land that the school currently occupies, as well as all the surrounding land of the Cape Fear Region. This is the very definition of long-term and the opposite of a “fad.” For Native American boys and men, wearing their hair long is traditional.

I explained the importance of my son’s hair to his religion and culture to school administrators, and I questioned how they could justify applying their short hair rule and no buns policy to boys only. But the administration denied my request for an exception for Logan from their policies. I begged the school to allow Logan to complete the last few months of first grade with his hair in a bun or braid. Again, they said no. As a parent, I am in the untenable position of having to disrupt the education of my first grader by changing his school abruptly during the school year — or I have to cause Logan significant spiritual, religious, and cultural harm by cutting his hair.

Cutting Logan’s hair is not an option. Logan’s hair is a part of him and our religious practice. His long hair carries his spirit; hair cutting cycles are part of our tribal ceremonies. Logan is a grass dancer and has danced in Native American powwows all over the United States. His hair is a part of his regalia and serves as a key element to the type of dancer he is. Without his hair, he will lose his spirit and connection to his dance.

Logan with his hair in a bun.

Ashley Lomboy

No student at a public charter school like Classical Charter Schools of Leland should be forced to cut their hair. For Logan, it’s a rejection of who he is and a demand that he sacrifice his culture and heritage to conform to baseless and unfair rules. This is an old tactic of exclusion and assimilation. At the Indian Boarding Schools, for many Native American students, one of the most immediate and devastating experiences of forced assimilation was having their long hair cut immediately following their arrival. In the present day, schools across the country have refused to allow Native American students to wear tribal regalia at school or even at their graduation, forcing them to hide a critical part of their identity.

As Native Americans, it is our job — every single day — to educate ourselves, the greater community, educational institutions, and every facet of society about why it is important to honor, acknowledge, and recognize who we are. This job is not something we are paid for, it’s not something we get a choice in, it is a fact of our everyday life. It is vital that my son’s school understands the importance of his hair and all it signifies. This learning cannot just be at a surface level, but at every level of administration, so my son does not feel shamed for his culture and religion at school or anywhere else.

This issue is not something my family, my local or extended tribal community across the country, my BIPOC community, or my trusted allies and partners take lightly. That’s why I submitted a letter to the school’s board of trustees to again explain the importance of Logan’s hair to our religion and culture, and to ask that he be allowed to continue his schooling as the proud Waccamaw Siouan boy that he is, braid and all.