At the ACLU, we know that students’ First Amendment rights don’t disappear at the schoolhouse gates. However, the Trump administration is attempting to challenge this and other constitutional rights by forcing schools to teach a curriculum that aligns with its political agenda.

This radical abuse of executive power follows more than four years of similar censorship efforts at the state and local level that have restricted, or prohibited, instruction about American history, race and gender. Terms like “indoctrination” and “cultural Marxism” are often trotted out to justify banning content from BIPOC or queer authors, and about the Black experience and LGBTQ life. From the Oval Office to local school libraries, educational censorship efforts have direct impacts on how students across the country are learning about our world.

“How can I expect these kids to interact with me as a human being, or view me as one, when they aren't taught the history of anyone besides themselves?”

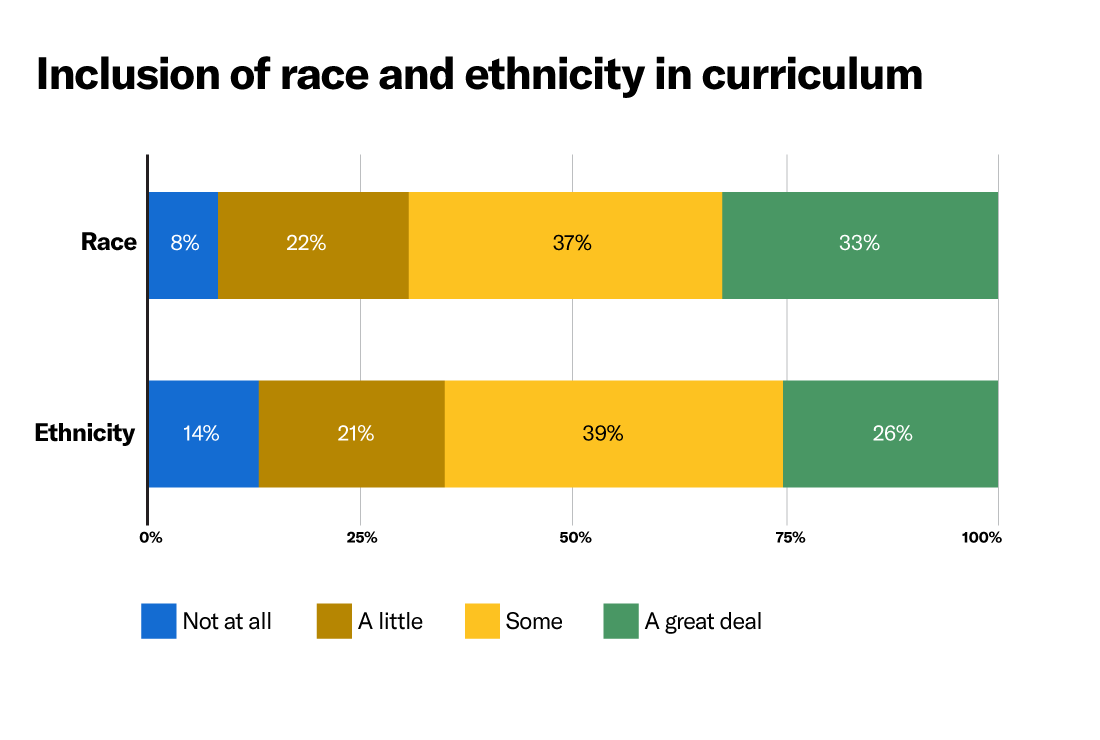

The ACLU's Youth Activism Research Collaborative asked students their thoughts on attempts to limit what they’re being taught in school. We surveyed 696 high school students from across the U.S and found that an overwhelming majority – 96 percent -- believe that a diverse education is critical. In spite of the massive support for a diverse education, not all students have access to curricula that uplift the realities of race, racism, sex and sexism in America. While 33 percent of students reported learning “a great deal” about racial injustice, 8 percent reported not learning it at all.

To better understand the content of what students were learning and how it impacts them, ACLU researchers and Youth Advisory Board members conducted a series of focus groups with 70 participants of the ACLU’s National Advocacy Institute. Some students indicated that their school either avoided discussions about race altogether or actively restricted content. They reported omissions of the experiences of Black Americans and other marginalized groups, and some noticed their teachers actively altering curriculum to comply with new state laws censoring the teaching of topics related to race. A student who went to school in Oklahoma noted, “...we were barely taught about the Trail of Tears that went directly through [my city], we were barely taught...to talk about the Tulsa race massacre, even though it happened 50 miles up the road from us. It was just a lot of omissions."

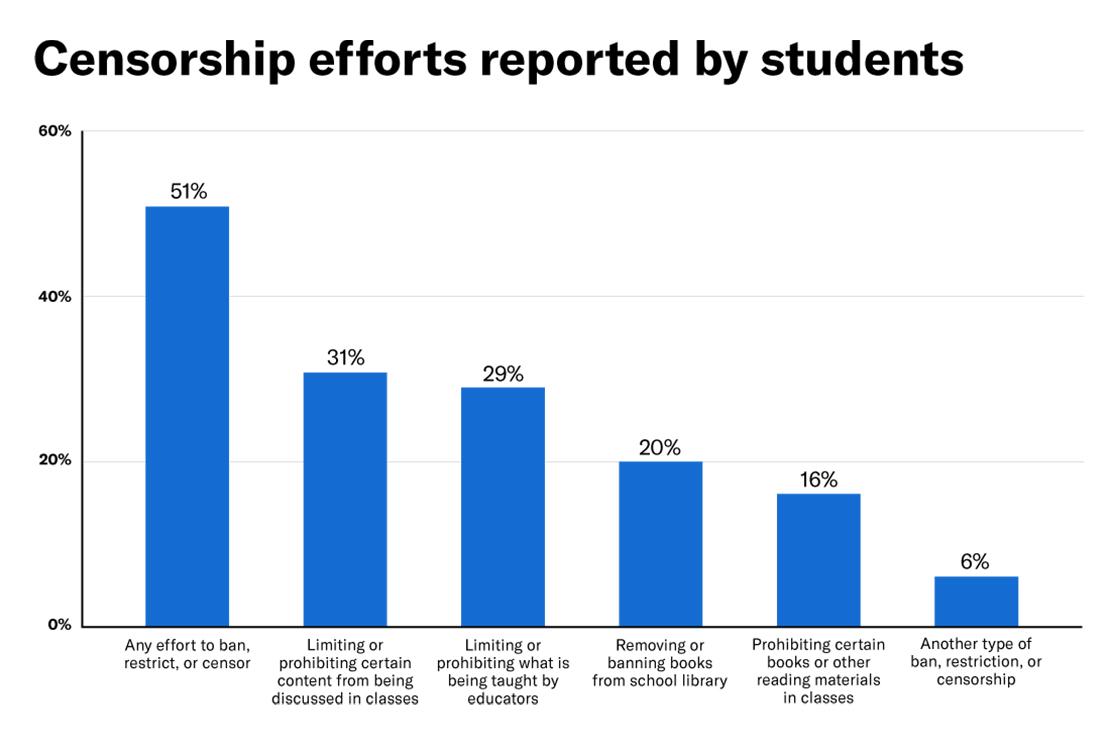

Twenty-nine percent of students surveyed noted efforts to restrict what content could be taught by educators, and 31 percent said attempts had been made to limit what could be discussed during class. One Florida student experienced the complexity of navigating education about race in a state with a classroom censorship law: “Some of my teachers wouldn’t have been able to support students in those types of conversations [about immigration and culture] anyway, but they were also prohibited from having them and could literally lose their jobs."

In some cases, students spoke positively about teachers proactively incorporating content about race, culture, and injustices into the curriculum in ways that fostered awareness and critical thinking. For example, a student from Montana shared that their teacher "encouraged dialogue in his classroom about the history of Latin American cultures, about imperialism, and the intersection of different cultures.” When discussing a book with a Mexican protagonist, one California student noted that "it's honestly, it's really, really transformative seeing a book where the author identifies with you and...the characters ... makes sense to you because they're going through the same things you're going through.”

“…we have full on bookshelves with caution tape on them. You can't read any of the books that are on them. We had teachers having to change their curriculum.”

More often teachers’ inclusion was described as too limited and selective, particularly with respect to Indigenous history, colonization, slavery, and the Civil Rights Movement. For example, a North Carolina student described their school’s teaching of racial justice history and racism as insufficient and an inaccurate representation of reality, stating “I don't really remember going into a lot of depth in school. It was like there was slavery and then racism and segregation, and then we ‘solved it, hooray.’” Several students also mentioned that teachers tend to highlight skewed perspectives on historical events and figures. A BIPOC Montana student indicated that though she had personally sought out information herself, she reported that many of her classmates, “have learned nothing beyond Martin Luther King's most diluted catchphrases. They hadn't learned anything about racism or racial violence, which really upset me.” She asked, “How can I expect these kids to interact with me as a human being, or view me as one, when they aren't taught the history of anyone besides themselves?”

In some cases, students described teachers’ attempts to address race as actively harmful, either because the teachers failed to fully understand the issues or they expressed discriminatory viewpoints. For example, a student described an advisor who addressed race as “not really important.” Similarly, another student said the teachers’ inclusions were “surface level” and lacking “heart.” Among the educators who dedicated time to the issue in the curriculum, some did so in misguided and or hurtful ways. One student shared their teacher’s attempt to teach about the realities of slavery, “he essentially did an exercise when we pretended that we were enslaved people and you were hiding throughout the school...There was one African American student in the class and ... I felt like it was hard for him probably to speak up. At the time I was like, why? ... what are we even learning from this?”

Some students indicated that teachers were silent on topics like race unless the students brought it up themselves, placing an unfair burden on students. As one student expressed, "I am here to learn. I'm not here to teach.” One student from Colorado took the initiative to suggest reading materials that center Asian characters to their Language Arts teacher and faced pushback: “My white teachers didn't talk about the fact that...a book about an Asian character didn't talk about race. ... [But] at least I knew that 30 kids were told to read it and that they could have had that perspective."

Students have also experienced bans on books and other education materials: 20 percent of high school students surveyed reported efforts to ban or remove books from their school libraries, while 16 percent reported efforts to prohibit certain books or reading materials in classrooms. That same Florida student described the lengths their school has gone to implement these policies: “…we have full on bookshelves with caution tape on them. You can't read any of the books that are on them. We had teachers having to change their curriculum.” A Texas student complained that their "school libraries were being removed and turned into ‘detention’ centers for students." These bans didn’t only effect books and curriculum: an Indiana student noted that “a teacher was made to take down their own classroom decorations that were deemed radical.”

Even if the censorship efforts are not successful, they may still limit students and teachers’ constitutional rights. As one student explained: "I think it makes teachers who would be willing to talk about issues that are even the slightest this controversial even more hesitant...Why discuss it if there might be a problem? So then you're ending up with no actual written restrictions, but just the general atmosphere of fear."

The survey suggests that far from being indoctrinated, students are hungry for more information about race and culture in the classroom, and they are eager for teachers to engage with their identities and histories in more tangible ways. As efforts at classroom censorship go national, it is critical that educators, administrators, and policymakers remember who loses when our histories and classrooms are politicized. Students are telling us that a lack of access to diverse, inclusive, and accurate curricula is damaging their education – and the first step to changing that is listening to them.

Students may be able to start banned book clubs and organize protests, but they shouldn’t have to do it alone. We all have a part to play to ensure that every student has the right to learn.

This research was conducted by members of ACLU's Youth Activism Research Collaborative: Emily Greytak and Sham Habteselasse, ACLU; Laura Wray-Lake, UCLA; and Elan Hope, Policy Research Associates; former ACLU interns Jada Cheek and Sunny Sun, and members of the Youth Advisory Board: Alan Flores, QIn Kramer, Valery Lenti-Navarro, Alexandra Miranda, Julia Squiterri and Khadijah Zahid. Lastly, we are grateful for the students who participated in this study, sharing their perspectives and experiences.