Few people know that paramedic ambulance services as we know them today originated in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in the 1960s. And even fewer know that a group of Black men organized and founded the country’s first emergency medical service (EMS). The Pittsburgh-based group, called Freedom House, wrote a training book that still serves as the basis for EMS training to this day, and pioneered life-saving practices in the field. Not everybody knows about this Black-led service that revolutionized emergency response, but I do: I served as a paramedic with Freedom House from 1972 to 1975.

An Alternative to Police as Emergency Responders

I’ll never forget the excitement I felt when I first traveled in an ambulance with its siren blaring, or the feeling of satisfaction when we’d drop patients off at the emergency room and let the doctors take it from there while we moved on to the next call. We were saving lives — Black lives. You see, back then, you had to rely on the police for medical emergencies, and unfortunately, there was not a good relationship between Black residents and the police, so we wouldn’t call them in emergencies. Even if we did call them, they often wouldn’t come to Black neighborhoods, at least not quickly. Freedom House was founded by and for Pittsburgh’s under-served Black community for that reason. And not everybody in Pittsburgh liked it.

The rest of the city’s residents had to rely on the police to respond to all emergency calls. When it came to medical and mental health emergencies, it was clear the police were not the right ones for the job. When police would transport a patient to the hospital, they’d throw them in the back of a police wagon while both officers sat up front. If something happened to you on the way, nobody would notice until you got to the emergency room, when it might be too late. Police didn’t have the medical training we did, and their vehicles didn’t have the equipment ours did — defibrillators, monitors, battery-powered EKGs. Sometimes our ambulances would pass by the police on our way to the hospital, beating them to the same place they were trying to get to.

The police were not equipped to respond to people in mental health crises, either. On one occasion, the police were called on a man screaming at people on the street. I actually knew the man; he was a former paramedic who had fallen on hard times and was suffering from mental health issues. So I got on the scene shortly after the police arrived and managed to calm him down and de-escalate the situation. If the police were left to respond, the outcome would not have been good.

It’s situations like these that show that a critical part of emergency response is compassion and community bonds. It’s easy to throw a person down and handcuff him and take him to jail without actually knowing why that person is acting out. Until first responders start making de-escalation a priority in all cases, then I think we will keep seeing the tragedies we see so often today, when a situation that is mild in nature escalates and a person ends up losing their life.

“It’s situations like these that show that a critical part of emergency response is compassion and community bonds.”

First responders need to see the communities they serve as allies. You need to have compassion and empathy for these communities; you need to build a level of confidence and trust that they will get care when they call you, not trouble.

Disbanding Freedom House

Freedom House ended up being a victim of its own success. When Pittsburgh’s white residents realized the Black community was getting better emergency care than they got from the police, they complained to the mayor. They didn’t want to rely on the police for emergency response. They wanted something like Freedom House. The mayor eventually caved to pressure and disbanded us.

As a consolation prize, the mayor agreed to hire Freedom House paramedics for a new service he started. Like many others, I joined the new EMS, but it was not the same. The new EMS paramedics refused to accept any type of training that we had to undergo. Even on call, I wasn’t allowed to do anything. I couldn’t talk on the radio. I couldn’t examine patients. I couldn’t treat them, nothing. I was the third person on a two-person crew. All the while, the city was buying them brand new vehicles and equipment — the same things that we had invented or put on our truck or tested.

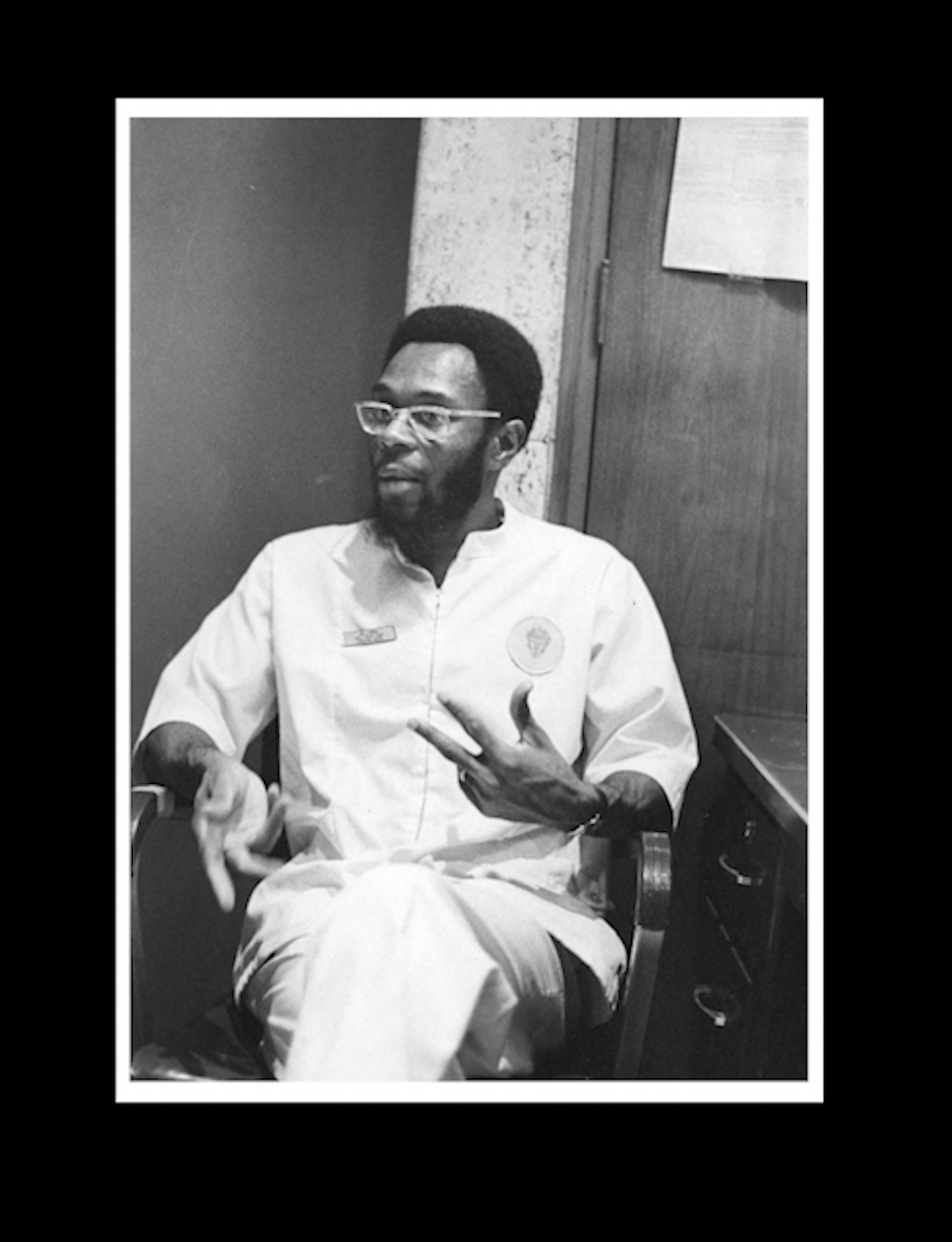

A photo of John Moon

Provided by the author

I almost threw my hands up and said, “Y’all got this, I’ll look someplace else.” But once I realized that the department was trying to prove that we were not qualified to do this kind of work, then I had to rethink my method of operation. I chose to step up my game, and became twice as good.

One time, we walked into a person’s home to find them unconscious, not breathing and with no heartbeat — they were in cardiac arrest, and if we didn’t do anything, the person was going to die. But the crew I was with didn’t know what to do. They didn’t have a clue. So they looked at me and said, “You take over.” I told one crew member to monitor the patient’s oxygen, the other to start CPR, and we ended up saving that person’s life. That wouldn’t have happened if they hadn’t asked me to take charge. From that point on, I decided that I was going to be a little bit more outspoken and take on a more proactive role in day-to-day operations of whichever unit I was working on.

The Erasure of Freedom House

Despite all our success and innovation, Freedom House has become a literal footnote in history. Freedom House published a book in 1977 that is required training for every paramedic in the country to this day. I came across the ninth edition in Tampa one day and flipped through. I read about the greatness of EMS in Miami and Jacksonville and Seattle and whatnot. The only mention of Freedom House is in a footnote saying only that we were a group of Black men that didn’t have an opportunity to get a high school education. What we did from 1967 to 1975 has been swept under the rug, has been forgotten or deleted from history.

“Despite all our success and innovation, Freedom House has become a literal footnote in history.”

That’s why it’s my heart’s desire to make sure that the legacy of Freedom House is made known to everyone in this country, especially members of today’s EMS. If I had my way, our history would be required reading for every EMS paramedic, EMT, and emergency physician in this country. They all need to know where the foundation of EMS began: as an alternative to police, in a Black community, led by Black people.