Voting should be as easy and convenient as possible, and in many cases it is. But across the U.S., too many politicians are passing measures making it harder to cast a ballot. The goal is to manipulate political outcomes, and the result is a severely compromised democracy that doesn’t reflect the will of the people. Our democracy works best when all eligible voters can participate and have their voices heard.

Suppression efforts range from the seemingly unobstructive, like voter ID laws and cuts to early voting, to mass purges of voter rolls and systemic disenfranchisement. And long before election cycles even begin, legislators can redraw district lines that determine the weight of your vote. Certain communities are particularly susceptible to suppression and in some cases, outright targeted — people of color, students, the elderly, and people with disabilities.

Below, we’ve listed some of the most rampant methods of voter suppression across the country — and the advocacy and litigation efforts aimed at protecting our fundamental right to vote.

Voter ID Laws

Thirty-six states have identification requirements at the polls. Seven states have strict photo ID laws, under which voters must present one of a limited set of forms of government-issued photo ID in order to cast a regular ballot – no exceptions. These strict ID laws are part of an ongoing strategy to suppress the vote, and it works. Voter ID laws have been estimated by the U.S. Government Accountability Office to reduce voter turnout by 2-3 percentage points, translating to tens of thousands of votes lost in a single state.

Over 21 million U.S. citizens do not have government-issued photo identification. That’s because ID cards aren’t always accessible for everyone. The ID itself can be costly, and even when IDs are free, applicants must incur other expenses to obtain the underlying documents that are needed to get an ID. This can be a significant burden on people in lower-income communities. Further, the travel required is an obstacle for people with disabilities, the elderly, and people living in rural areas.

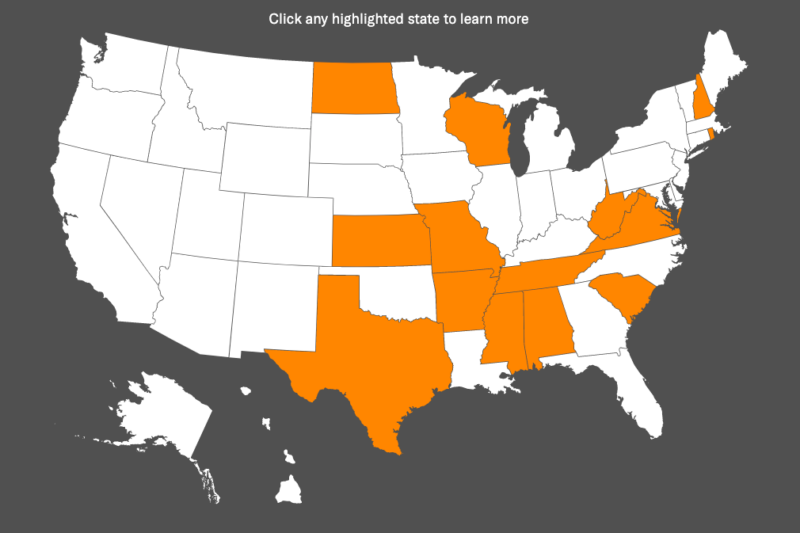

Voter ID restrictions imposed since 2010

Thirty-six states have identification requirements at the polls, including seven states with strict photo ID laws.

Resources on voter ID laws

Blogs | Litigation | Look up your state’s voter ID laws | Fact Sheet

Voter Registration Restrictions

Restricting the terms and requirements of registration is one of the most common forms of voter suppression. Restrictions can include requiring documents to prove citizenship or identification, onerous penalties for voter registration drives or limiting the window of time in which voters can register.

Politicians often use unfounded claims of voter fraud to try to justify registration restrictions. In 2011, Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach championed a law requiring Kansans to show “proof of citizenship” documents in order to register to vote, citing false claims of noncitizen voting. Most people don’t carry the required documents on hand — like a passport, or a birth certificate — and as a result, the law blocked over 30,000 Kansans from voting. The ACLU sued and defeated the law in 2018.

Some states restrict registration by allowing people to register long in advance of an election. For example, New York requires voters to register at least 25 days before the election, which imposes an unnecessary burden on the right to vote. By forcing voters to register before the election even becomes salient to the public, it discourages people from registering in the first place. These outdated restrictions — which were designed for a time when registration forms were exclusively completed with pen and paper, and transmitted via snail mail — can significantly impact voter participation. In the 2016 presidential election, over 90,000 New Yorkers were unable to vote because their applications did not meet the 25-day cutoff, and the state had the eighth-worst turnout rate in the country.

Resources on voter registration restrictions

Blogs | Look up your state’s voter registration requirements | States with online voter registration

Voter Purges

Cleaning up voter rolls can be a responsible part of election administration because many people move, die, or become ineligible to vote for other reasons. But sometimes, states use this process as a method of mass disenfranchisement, purging eligible voters from rolls for illegitimate reasons or based on inaccurate data, and often without adequate notice to the voters. A single purge can stop up to hundreds of thousands of people from voting. Often, voters only learn they’ve been purged when they show up at the polls on Election Day.

Voter purges have increased in recent years. A recent Brennan Center study found that almost 16 million voters were purged from the rolls between 2014 and 2016, and that jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination — which are no longer subject to preclearance after the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act — had significantly higher purge rates.

The most common excuses for purging voter rolls are to filter out voters who have changed their address, died, or have failed to vote in recent elections. States often conduct such purges using inaccurate data, booting voters who don’t even fall under the targeted category. In 2016, Arkansas purged thousands of voters for so-called felony convictions, even though some of the voters had never been convicted of a felony at all. And in 2013, Virginia purged 39,000 voters based on data that was later found to have an error rate of up to 17 percent.

Resources on voter purges

Blogs | Report: Purges: A Growing Threat to the Right to Vote

Felony Disenfranchisement

A felony conviction can come with drastic consequences including the loss of your right to vote. But different states have different laws. Some ban voting only during incarceration. Some ban voting for life. Some ban people while on probation or parole; other ban people from voting only while incarcerated. And some states, like Maine and Vermont, don’t disenfranchise people with felony convictions at all. The fact that these laws vary so dramatically only adds to the overall confusion that voters face, which is a form of voter suppression in itself.

Due to racial bias in the criminal justice system, felony disenfranchisement laws disproportionately affect Black people, who often face harsher sentences than white people for the same offenses. It should come as no surprise that many of these laws are rooted in the Jim Crow era, when legislators tried to block Black Americans’ newly won right to vote by enforcing poll taxes, literacy tests, and other barriers that were nearly impossible to meet.

To this day, the states with the most extreme disenfranchisement laws also have long records of suppressing the rights of Black people. In Iowa, a system of permanent disenfranchisement, paired with the most disproportionate incarceration rate of Black people in the nation, has resulted in the disenfranchisement of an estimated one in four voting-age black men.

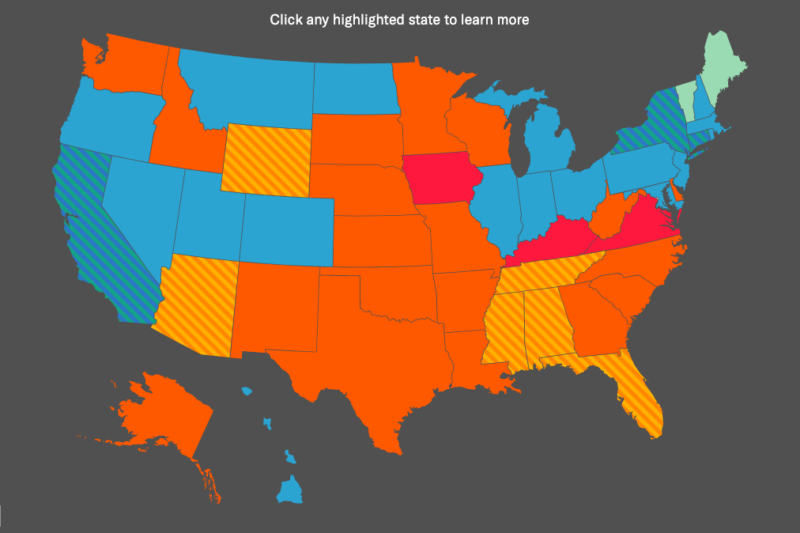

Felony disenfranchisement laws by state

A patchwork of state felony disfranchisement laws, varying in severity from state to state.

Resources on felony disenfranchisement

Blogs | Litigation | Podcast: Desmond Meade and Dale Ho on restoring the right to vote

Gerrymandering

Every 10 years, states redraw district lines based on population data gathered in the census. Legislators use these district lines to allocate representation in Congress and state legislatures. When redistricting is conducted properly, district lines are redrawn to reflect population changes and racial diversity. But too often, states use redistricting as a political tool to manipulate the outcome of elections. That’s called gerrymandering — a widespread, undemocratic practice that’s stifling the voice of millions of voters.

How it all begins

Redistricting is front and center in 2020. In April, the Trump administration will conduct the 2020 census and states will use its results to redraw district lines across the country. Those new district lines will determine our political voice for the next decade.

It’s no coincidence that the administration — which has a lengthy track record on voter suppression and attacking immigrants — wanted to add a citizenship question to the census. The goal was to reduce census participation by immigrant communities, thereby stunting their growing political influence and depriving them of economic benefits.

Some might wonder what the problem is in adding a citizenship question to the census. But the purpose of the census is to count everybody in this country, citizens and noncitizens alike. Accurate population data is essential in apportioning representation and public funds. By trying to suppress participation, the administration made clear that it doesn’t want certain people to count — namely immigrants and even citizens who live in mixed-status households, who might have hesitated to participate if the Administration had succeeded in adding a citizenship question to the Census.

The ACLU sued the Trump administration over the citizenship question and successfully blocked it last year. In the process, we uncovered documents proving that attacking immigrants was the administration’s goal all along, and that Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross lied to Congress to hide it.

The 2020 census will no longer include a citizenship question — but the administration’s attempt to add it is yet another example of how politicians can use redistricting to suppress and manipulate the vote.

How the GOP manipulated Ohio elections

Resources on redistricting and gerrymandering

Blogs | Litigation | Look up the history of your district lines

Who’s Affected By Voter Suppression?

The short answer is all of us. Our democracy is debased when the vote is not accessible for all. But the fact is that some groups are disproportionately affected by voter suppression tactics, including people of color, young people, the elderly, and people with disabilities. There’s proof that certain groups have been deliberately targeted — for example, the government documents uncovered in the census case proved that the citizenship question intended to harm immigrants. Other times, the proof is in the numbers.

- Seventy percent of Georgia voters purged in 2018 were Black.

- Across the country, one in 13 Black Americans cannot vote due to disenfranchisement laws.

- One-third of voters who have a disability report difficulty voting.

- Only 40 percent of polling places fully accommodate people with disabilities.

- Across the country, counties with larger minority populations have fewer polling sites and poll workers per voter.

- Six in ten college students come from out of state in New Hampshire, the state trying to block residents with out of state drivers’ licenses.

How To Protect Your Vote

The right to vote is the most fundamental constitutional right for good reason — democracy cannot exist without the electoral participation of citizens. We vote because it’s we, the people, who are supposed to shape our government. Not the other way around.

States can enact measures to encourage rather than suppress voting. Automatic, online, and same-day voter registration encourage participation and reduce chances of error. Early voting helps people with travel or accessibility concerns participate. And states must enforce the protections of the Voting Rights Act.

At an individual level, the best way to fight voter suppression is to vote. Here’s how to ensure your vote is protected:

- Tell your senators to pass the VRAA, which would reinstate critical protections against voter suppression left behind after the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in 2013.

- Know Your Rights before you get to the polling booth. Here’s a guide on what to do if you face registration issues, need disability or language accommodations, or come across someone who’s interfering with your right to vote. Share the guide on Facebook and Twitter to spread the word.

Leila Rafei, Content Strategist, ACLU